Spay-Neuter Adverse Effects AVMA on resulting urinary, ligament, bone, obesity, cancer, thyroid, etc.

SPAY & NEUTER MEDICAL FACTS

The American Veterinary Medical Association official policy says

“Mandatory spay-neuter is a bad idea.”

The AVMA has taken this stance in direct contradiction to the Humane Society (HSUS) stated goals.

http://www.thedogplace.org/Veterinary/09051-Spay-Neuter_Andrews.asp

Barbara (BJ) Andrews © TheDogPlace May 2009 - AVMA policy is particularly brave because the AVMA is under assault by the newest of the Humane Society’s creations, the HSVA. The AVMA boasts over 70,000 members. No one knows how many members the Humane Society Veterinary Assoc. actually has but with millions of non-taxable HSUS dollars behind it, the Humane Society Vets will probably prevail.

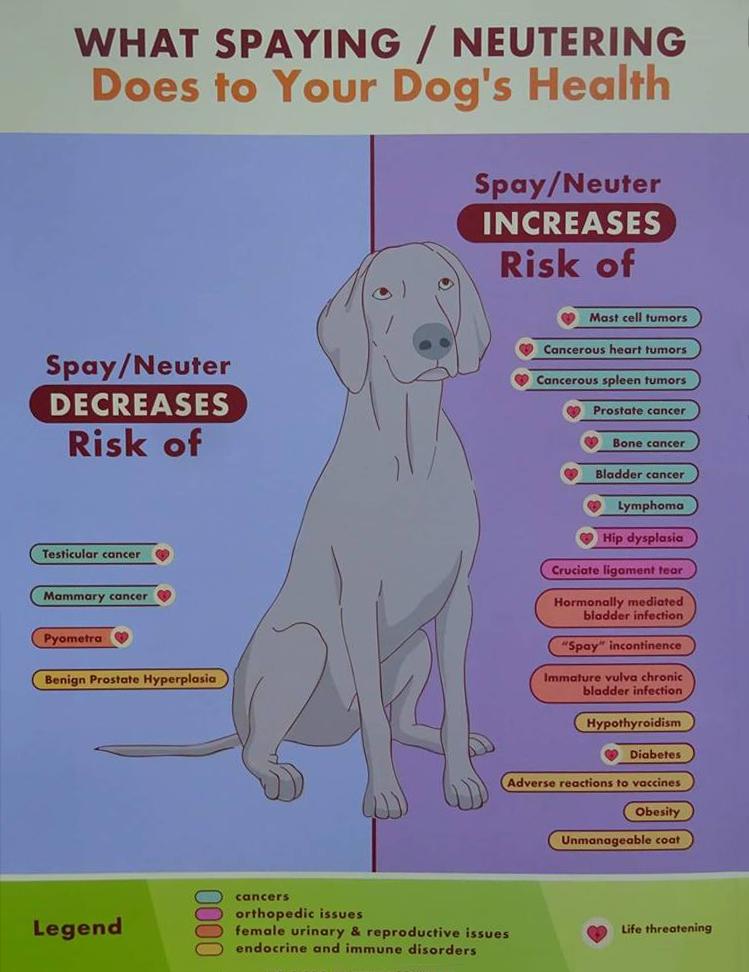

Even so, the AVMA deals HSUS a blow in its straightforward policy statement “potential health problems associated with spaying and neutering have also been identified, including an increased risk of prostatic cancer in males; increased risks of bone cancer and hip dysplasia in large-breed dogs associated with sterilization before maturity; and increased incidences of obesity, diabetes, urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and hypothyroidism.” Ref: AVMA.org

Whether/when to spay or neuter has been studied by various veterinary groups. Linda Witouski, TheDogPress Legislative Editor, compiled this 2008 summary report:

In a study of well over a million dogs, information on breed, sex, and age was collected and reported to the Veterinary Medical Database between 1964 and 2003. Results—Castrated male dogs were significantly more likely than other dogs to have hip dysplasia (CHD) than other dogs and spayed females were significantly more likely to have cranial cruciate ligament deficiency (CCLD).

Dogs up to 4 years old were significantly more likely to have HD whereas dogs over 4 years old were significantly more likely to have CCLD. In general, large- and giant-breed dogs were more likely than other dogs to have HD, CCLD, or both.

Prevalence of HD and CCLD increased significantly over the 4 decades for which data were examined. There was no data reflecting the decade-by-decade increase but one might suspect that the significantly increased rate of spay and castration procedures may be a factor in the overall forty-year increase. ref: June 15, 2008 Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association

There is unquestioned benefit to spay and castration but it may be a human benefit rather than of any tangible benefit to the canine.

There are other adverse effects of surgical neutering, particularly when the surgery is performed on puppies, obliquely referred to as “early-age” spay/neuter, pediatric spay/neuter, or juvenile spay/neuter, presumably depending on age at which ovariohysterectomy or orchietomy is performed on the puppy. A study published in the Journal of Am. Veterinary Medicine, noted an “increased rate of cystitis and decreasing age at gonadectomy was associated with increased rate of urinary incontinence. Among male and female dogs with early-age gonadectomy, hip dysplasia, noise phobias, and sexual behaviors were increased, whereas obesity, separation anxiety, escaping behaviors, inappropriate elimination when frightened…”

These are not insignificant problems. Urinary incontinence and uncontrolled elimination will banish a dog to the outdoors and more often than not, to the “shelter.” Hip dysplasia, worsened by obesity, will bring valued family dogs in to the veterinary office where costly hip surgery may be performed. Other dogs, owned by families of lesser means or smaller hearts, will be dumped at the pound. The same can be said of dogs with noise phobias, separation anxieties, and embarrassing sexual behaviors. Dogs that habitually escape will inevitably be run over or taken to the local shelter.

While all agree that surgical castration and hysterectomy are the only viable options for sterilization, Chris Zink DVM, PhD, DACVP explains risks for the canine athlete, covering the subject in an easy to read format.

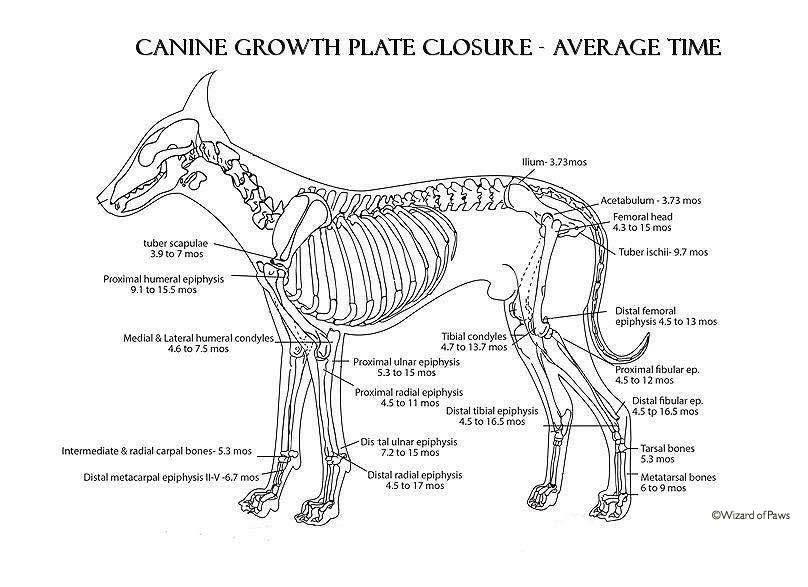

In summary, our Health Editors and knowledgeable breeders agree; pets should be spayed or neutered but not until growth plates have closed and then only if their behavior becomes an annoyance to the family. Note that age of puberty varies depending on breed growth rate.

Thanks to the Animal Rights Extremist (ARE) and the Humane Society of the U.S. (HSUS), none of which rescue, adopt, or shelter unwanted dogs, it is almost impossible to adopt a shelter pet that isn’t already spayed or castrated. Like the surgery itself, that situation has benefits and drawbacks for adoptive owners. The spay/neuter policy has virtually no benefit to the cat or dog other than to prevent pregnancy. Unwanted pregnancy can be prevented by keeping the animal inside the home or a secure fence.

By the way, an electric fence does not prevent other dogs from getting to your dog!

Whether and When to have surgical sterilization performed should be up to the owner, not the government or local bureaucrats. Who knows more about your dog’s health than your veterinarian? Even though promoting early spay and neuter profits vets in the long run; honest, knowledgeable vets who learn from clinical experience and vet school instead of animal “rights” activists will veto early spay/neuter.

So talk to your vet. Then contact a responsible breeder who is as knowledgeable as your good vet. Breeders have been a little bit brainwashed but if you convince them that you want only to delay premature, risky removal of sex hormone organs, they will listen. By far, your best best is a purebred puppy or retired adult from a knowledgeable breeder.

Your choice should not be limited to a shelter mongrel with unpredictable size and personality, one that may or may not fit your family; one that has been subjected to surgical sterilization resulting in serious side effects. The choice should be yours and it should be an informed choice, not an automatic compliance of something you don't understand, the results of which could keep you in and out of the vet's office for a lifetime!

Early Spay/Neuter warns of adverse physical effects when sterilized before 6 months of age.

SPAY & NEUTER COMMON SENSE

Early Spay-Neuter Considerations for the Canine Athlete

|

|

When humans undergo surgical sterilization without follow up hormone replacement therapy (HRT) they suffer serious physical and mental health problems. This medical fact should give dog owners pause for thought before spaying or neutering as a matter of convenience. Ask your vet if hormone therapy is available for spayed and neutered pets. He'll laugh.

Early Spay-Neuter Considerations for the Canine Athlete

courtesy of Canine Sports Productions by Chris Zink DVM, PhD, DACVP

Orthopedic Considerations

A study by Salmeri et al in 1991 found that bitches spayed at 7 weeks grew significantly taller than those spayed at 7 months, and that those spayed at 7 months had significantly delayed closure of the growth plates than those not spayed (or presumably spayed after the growth plates had closed).(1) A study of 1444 Golden Retrievers performed in 1998 and 1999 also found bitches and dogs spayed and neutered at less than a year of age were significantly taller than those spayed or neutered at more than a year of age.(2) The sex hormones promote the closure of the growth plates, so the bones of dogs or bitches neutered or spayed before puberty continue to grow. Dogs that have been spayed or neutered well before puberty can frequently be identified by their longer limbs, lighter bone structure, narrow chests and narrow skulls. This abnormal growth frequently results in significant alterations in body proportions and particularly the lengths (and therefore weights) of certain bones relative to others. For example, if the femur has achieved its genetically determined normal length at 8 months when a dog gets spayed or neutered, but the tibia, which normally stops growing at 12 to 14 months of age continues to grow, then an abnormal angle may develop at the stifle. In addition, with the extra growth, the lower leg below the stifle becomes heavier (because it is longer), causing increased stresses on the cranial cruciate ligament. These structural alterations may be the reason why at least one recent study has shown that spayed and neutered dogs have a higher incidence of CCL rupture.(3) Another recent study showed that dogs spayed or neutered before 5 1/2 months had a significantly higher incidence of hip dysplasia than those spayed or neutered after 5 1/2 months of age.(4) Breeders of purebred dogs should be concerned about these two studies and particularly the latter, because they might make incorrect breeding decisions if they consider the hip status of pups they bred that were spayed or neutered early.

Cancer Considerations

There is a slightly increased risk of mammary cancer if a female dog has one heat cycle. But my experience indicates that fewer canine athletes develop mammary cancer as compared to those that damage their cranial cruciate ligaments. In addition, only about 30 % of mammary cancers are malignant and, as in humans, when caught and surgically removed early the prognosis is very good.(5) Since canine athletes are handled frequently and generally receive prompt veterinary care, mammary cancer is not quite the specter it has been in the past. A retrospective study of cardiac tumors in dogs showed that there was a 5 times greater risk of hemangiosarcoma, one of the three most common cancers in dogs, in spayed bitches than intact bitches and a 2.4 times greater risk of hemangiosarcoma in neutered dogs as compared to intact males.(6) A study of 3218 dogs demonstrated that dogs that were neutered before a year of age had a significantly increased chance of developing bone cancer, a cancer that is much more life-threatening than mammary cancer, and that affects both genders.(7) A separate study showed that neutered dogs had a two-fold higher risk of developing bone cancer.(8) Despite the common belief that neutering dogs helps prevent prostate cancer, at least one study suggests that neutering provides no benefit.(9)

Behavioral Considerations

The study that identified a higher incidence of cranial cruciate ligament rupture in spayed or neutered dogs also identified an increased incidence of sexual behaviors in males and females that were neutered early.(3) Further, the study that identified a higher incidence of hip dysplasia in dogs neutered or spayed before 5 1/2 months also showed that early age gonadectomy was associated with an increased incidence of noise phobias and undesirable sexual behaviors.(4) A recent report of the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation reported significantly more behavioral problems in spayed and neutered bitches and dogs. The most commonly observed behavioral problem in spayed females was fearful behavior and the most common problem in males was aggression.(10) Yet another study showed that unneutered males were significantly less likely than neutered males to suffer cognitive impairment when they were older.(11) Females were not evaluated in that study.

Other Health Considerations

A number of studies have shown that there is an increase in the incidence of female urinary incontinence in dogs spayed early.(12) Interestingly, neutering also has been associated with an increased likelihood of urethral sphincter incontinence in males.(13) This problem is an inconvenience, and not usually life-threatening, but nonetheless one that requires the dog to be medicated for life. A health survey of several thousand Golden Retrievers showed that spayed or neutered dogs were more likely to develop hypothyroidism.(2) This study is consistent with the results of another study in which neutering and spaying was determined to be the most significant gender-associated risk factor for development of hypothyroidism.(14) Infectious diseases were more common in dogs that were spayed or neutered at 24 weeks or less as opposed to those undergoing gonadectomy at more than 24 weeks.(15) Finally, the AKC-CHF report demonstrated a higher incidence of adverse reactions to vaccines in neutered dogs as compared to intact.(10)

For these reasons, I have significant concerns with spaying or neutering dogs before puberty, particularly for the canine athlete. And frankly, if something were healthier for the canine athlete, would we not also want that for pet dogs as well? But of course, there is the pet overpopulation problem. How can we prevent the production of unwanted dogs while still leaving the gonads to produce the hormones that are so important to canine growth and development? The answer is to perform vasectomies in males and tubal ligation in females, to be followed after maturity by ovariohysterectomy in females to prevent mammary cancer and pyometra. One possible disadvantage is that vasectomy does not prevent some unwanted behaviors associated with males such as marking and humping. On the other hand, it has been my experience that females and neutered males actively participate in these behaviors too. Really, training is the best solution for these issues. Another possible disadvantage is finding a veterinarian who is experienced in performing these procedures. Nonetheless, some do, and if the procedures were in greater demand, more veterinarians would learn them.

I believe it is important that we assess each situation individually. If a pet dog is going to live with an intelligent, well-informed family that understands the problem of pet overpopulation and can be trusted to keep the dog under their control at all times and to not breed it, I do not recommend spaying or neutering before 14 months of age. In the case of dogs that might be going to less vigilant families, vasectomy and tubal ligation will allow proper growth while preventing unwanted pregnancies.

related link: 2009 Vet Assoc. Update, more health damage...

http://www.thedogplace.org/Veterinary/0603-SpayNeuter_Zink.asp #11033

References:

1. Salmeri KR, Bloomberg MS, Scruggs SL, Shille V.. Gonadectomy in immature dogs: effects on skeletal, physical, and behavioral development. JAVMA 1991;198:1193-1203

2. http://www.grca.org/pdf/health/healthsurvey.pdf

3. Slauterbeck JR, Pankratz K, Xu KT, Bozeman SC, Hardy DM. Canine ovariohysterectomy and orchiectomy increases the prevalence of ACL injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Dec;(429):301-5.

4. Spain CV, Scarlett JM, Houpt KA. Long-term risks and benefits of early-age gonadectomy in dogs. JAVMA 2004;224:380-387.

5. Meuten DJ. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 4th Edn. Iowa State Press, Blackwell Publishing Company, Ames, Iowa, p. 575

6. Ware WA, Hopper DL. Cardiac tumors in dogs: 1982-1995. J Vet Intern Med 1999 Mar-Apr;13(2):95-103

7. Cooley DM, Beranek BC, Schlittler DL, Glickman NW, Glickman LT, Waters D, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Nov;11(11):1434-40

8. Ru G, Terracini B, Glickman LT. Host related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma. Vet J. 1998 Jul;156(1):31-9.

9. Obradovich J, Walshaw R, Goullaud E. The influence of castration on the development of prostatic carcinoma in the dog. 43 cases (1978-1985). J Vet Intern Med 1987 Oct-Dec;1(4):183-7

10. http://www.akcchf.org/pdfs/whitepapers/Biennial_National_Parent_Club_Canine_Health_Conference.pdf

11. Hart BL. Effect of gonadectomy on subsequent development of age-related cognitive impairment in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001 Jul 1;219(1):51-6.

12. Stocklin-Gautschi NM, Hassig M, Reichler IM, Hubler M, Arnold S. The relationship of urinary incontinence to early spaying in bitches. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 57:233-6, 2001

13. Aaron A, Eggleton K, Power C, Holt PE. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in male dogs: a retrospective analysis of 54 cases. Vet Rec. 139:542-6, 1996

14. Panciera DL. Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987-1992). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 204:761-7 1994

15. Howe LM, Slater MR, Boothe HW, Hobson HP, Holcom JL, Spann AC. Long-term outcome of gonadectomy performed at an early age or traditional age in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001 Jan 15;218(2):217-21

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rethinking Spay & Neuter, 2011 spay/neuter study reveals shorter life span, higher vet bills, hormone & health problems, contradicting pet sterilization campaign!

http://www.thedogplace.org/Veterinary/Spay-Neuter-1101_Coats.asp

RETHINKING SPAY & NEUTER

By Geneva Coats R.N., TheDogPlace.org Genetics Editor / January 2011

Is Pet sterilization a purely beneficial routine procedure? Most breeders today sell companion puppies under contracts requiring spay or neuter as a condition of sale. [6]

Ingrained in current culture is the notion of pet overpopulation and to prevent the deaths of animals in shelters all pets should be sterilized. To bolster that campaign, we are told that a sterilized pet is happier, healthier and longer-lived than one who remains intact. What are the facts?

"PET OVERPOPULATION"

In the mid-twentieth century, there was an abundance of pets; many were available “free to good home” via newspaper ads. Few pets were sterilized, and many people unwisely allowed their dogs to roam the neighborhood, producing unplanned litters.

According to “Maddie’s Fund” president Richard Avanzino, in the 1970s, our country’s animal control agencies were killing, on average, about 115 dogs and cats annually for every 1000 human residents. This amounted to about 24 million shelter deaths every year.2 Avanzino is also the former executive director of the San Francisco SPCA, and is regarded by many as the founder of the modern no-kill movement in the US.

"The Problem" of too many pets and not enough homes to go around began a huge campaign based on spaying and neutering pets. Vets began to routinely urge clients to sterilize their pets as an integral part of being a “responsible owner”. Planned breeding became a politically incorrect activity. A popular slogan today is “Don’t breed or buy, while shelter dogs die.”

The crusade for spaying and neutering pets has been very successful. A 2009-2010 national pet owners’ survey by the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association reveals that the vast majority of owned pets...75% of dogs and 87% of cats... are spayed or neutered. (As reported by the HSUS in Dec. 2009):

In recent years, according to Avanzino, annual shelter death numbers have dramatically declined to about 12 per thousand human residents, or about 3.6 million deaths each year. This amounts to a staggering 85% reduction in killing since the 1970s.2 We have reached a nationwide pet shelter death rate averaging just 1.2% per population, effectively a “no kill” rate.

Feral cats and kittens account for the majority of shelter numbers9 but many areas have actual shortages of adoptable dogs, particularly purebreds and puppies, and must import from other regions to fill the need. Dogs are being smuggled into the US by the thousands with rescue groups importing small dogs from Mexico, Brazil, the Caribbean, Taiwan and Romania, to name some of the most popular points of origin. The conservative estimate is that 300,000 dogs are imported into the US each year to meet the demand for pets.3

According to shelter expert Nathan Winograd, every year in this country, approximately 3 million adoptable pets die in shelters.* At the same time, around 17 million US households are looking for a new pet. That is 17 million households above and beyond those who already will adopt a shelter or rescue pet. There are nearly six times as many homes opening up every year as the number of adoptable pets killed in shelters!8 It seems the greatest challenge these days is to find ways to match up the adoptable pets with the homes that are waiting for them. Breed rescues fill this niche admirably, but are privately funded and desperately in need of assistance in order to be able to effectively perform this service. Perhaps some of the public funds budgeted for shelters to kill animals could be better spent helping rescue groups who are proactive in matching adoptable pets to suitable homes.

SPAY/NEUTER AND HEALTH

Now that we have addressed the issue of pet overpopulation, let’s examine the claim that sterilization surgery promotes better health. While there are some benefits to sterilization, there are some drawbacks as well.

Sterilization will naturally serve to prevent any unwanted litters. In bitches, spaying will greatly reduce the risk of breast cancer, pyometra, perianal fistula and cancers of the reproductive organs.5

Spay surgery itself carries a somewhat high rate (around 20%) of complications such as infection, hemorrhage and even death.5 Spaying significantly increases the rate of urinary incontinence in bitches….about 20-30% of all spayed bitches will eventually develop this problem. This is believed to be most likely caused by the lack of estrogen that results from being spayed.1

Sterilization of males may reduce some unwanted sexual behaviors, but there are few other proven benefits to neutering a male dog. Testicular cancer is prevented, but the actual risk of that cancer is extremely low (<1%) among intact dogs. Contrary to popular belief, studies show that the risk of prostate cancer is actually HIGHER in neutered dogs than in their intact counterparts.5

Several studies prove significant health risks associated with sterilization, particularly when done at an early age. The most problematic is a delayed closure of the bony growth plates. This results in an abnormal, “weedy” skeletal development that increases the incidence of orthopedic problems like hip dysplasia and patellar luxation. Working and performance dogs, if neutered before maturity, risk the inability to perform the jobs they were bred for.10

But by far the most startling news to surface this year is the result of a study that shows that keeping ovaries to the age of six years or later is associated with a greater than 30% increase of lifespan in female Rottweilers.4 Similar studies in humans reinforce this finding.7,11

A 30% longer lifespan means that you could have many additional years with your bitch simply by delaying spay surgery until middle-age or later.

Behavioral studies show that sterilization increases fearfulness, noise phobias and aggression. Other well-documented adverse health effects of de-sexing include increased risk of bone cancer, hemangiosarcoma, hypothyroidism, and cognitive dysfunction in older pets. Sterilization confers an increased susceptibility to infectious disease, and also a higher incidence of adverse reactions to vaccines.10

So there is no need to feel obligated to sterilize for health or welfare reasons. But what about the need to protect the puppies that we sell from unethical breeders?

PUPPY SALES CONTRACTS

Many breeders are justifiably very concerned about their dogs being subjected to neglect or abuse by falling into disreputable hands. To help prevent such situations, it has become commonplace for breeders to include spay/neuter requirements in their pet sales contract, and/or to sell the dog on a limited registration. Another common stipulation, particularly for a show/breeding dog, is requiring that the dog be returned to the seller in the event the buyer no longer wishes to keep him.6

Such contracts are highly effective when selling a puppy to someone who is honest and ethical. However, contracts are easily skirted by the unscrupulous, particularly if the buyer lives in a different region. Someone intent on breeding may do so regardless of contract language, and then sell the puppies without registration. And without personal knowledge of the living conditions at your puppy’s new home, it is impossible to predict what sort of care and attention he or she will receive. Even some show breeders may have very different ideas on what constitutes proper care. There is no substitute for a home check to follow up that initial puppy application!

Bottom line, the best insurance for your puppies is making sure that you get to know the buyer personally. If something about the buyer or his attitude doesn’t seem right, then it’s probably best to cancel the sale. If you want to sell puppies on spay-neuter agreements you might consider advising the buyer to wait until the puppy reaches maturity before having sterilization surgery performed. Another idea is to ask your vet if vasectomy would be a viable alternative to castration for your male. This would preserve sex hormones and possibly prevent some of the adverse health effects of castration.

PUREBRED GENE POOLS

Sterilization of all dogs sold as companions may have some unintended adverse effects. The nature of breeding for the show ring involves intense selection that severely narrows the gene pool in many, if not most, breeds. Some breeds started with just a small pool of founders. Through the years, overuse of only a few popular sires further reduced the genetic variety available in the breed. When troublesome health problems surface and become widespread, where can we turn for “new blood”?

The show-bred population of a breed may have become too small as a result of intense inbreeding or the genetic bottleneck created by overuse of popular sires; or the breed gene pool may have become genetically depleted because of unwise selection for specific, sometimes unhealthy physical traits favored in the show ring. As a result, dogs from the “pet” population may actually be the salvation of the breed gene pool.

Trying to guess which dogs are the "best" to keep intact for showing and breeding can be hit-or-miss. Imagine the scenario where a successful show dog eventually develops a heritable health issue, while his brother is much healthier...but brother was neutered long ago, thereby eliminating those good genes forever. What about that Champion's non-show quality sister, who has good health, great mothering instincts and the genetic ability produce exceptional offspring? If sold as a spayed companion, her genes are effectively lost.

And what about the very future of the dog fancy? Many people (myself included) bought an intact dog as a pet, and only later sparked an interest in showing and breeding. Developing new breeders is critical to the survival of our sport, but if we sell all companions on spay/neuter agreements, we will lose many fanciers before they have the chance to discover the joy of dog breeding and showing!

Sadly, mandatory sterilization laws are sweeping the nation and may further compromise the future of the dog fancy. AKC registrations continue to decline and the push to legally and/or contractually require spay and neuter of most every dog will only worsen that situation.

Regardless, there is a huge demand in society for healthy pets; a demand which the responsible breeders could not come close to meeting even if they wanted to...and sometimes, they do not want to. The choice we have as a society is how that demand will be filled. Many believe that only responsible people should be allowed to keep intact dogs and breed on a limited basis. However, the attempt to legally force well-regulated and inspected commercial breeders and the casual small home breeders out of the picture leaves only the unregulated, less visible "underground" producers and smugglers to fill the need for pets. Perhaps it is time to re-think our preconceived notions about who should and shouldn't possess intact dogs!

As a dog owner, one must weigh the risks of sterilization against the benefits in order to make that very personal decision. Popular culture and many veterinarians downplay or even ignore the risks involved with spay/neuter because of their own belief in the need to reduce dog breeding in general. Many people still believe that overpopulation remains a pressing concern and that sterilization always promotes better health. Some even believe that breeding a female is abusive. It seems the animal rights groups have done an excellent job of brainwashing the public on these matters!

As breeders, we may be wise to re-examine the routine request to have all our companion puppies spayed or neutered. The future availability of pets, the perpetuation of the dog fancy, the health of the individual dogs and the gene pools of the breeds that we love may all depend on keeping a few more dogs intact!

*An adoptable pet is one that does not have insurmountable health or temperament issues. Per California’s Hayden law: The California Legislature Defines No-Kill Terms ■ California Law, SB 1785 Statutes of 1998, also known as "The Hayden Law" has defined no-kill terms.

What is Adoptable? 1834.4. (a) "No adoptable animal should be euthanized if it can be adopted into a suitable home. Adoptable animals include only those animals eight weeks of age or older that, at or subsequent to the time the animal is impounded or otherwise taken into possession, have manifested no sign of a behavioral or temperamental defect that could pose a health or safety risk or otherwise make the animal unsuitable for placement as a pet, and have manifested no sign of disease, injury, or congenital or hereditary condition that adversely affects the health of the animal or that is likely to adversely affect the animal's health in the future."

Adoptable dogs may be old, deaf, blind, disfigured or disabled.

http://www.thedogplace.org/Veterinary/Spay-Neuter-1101_Coats.asp

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

1 Bovsun, Mara; "Puddle Jumping; Canine Urinary Incontinence"; AKC Gazette April 2009

barkingbulletin.com/newsletter/2009/q4/Puddle-Jumping--Canine-Urinary-Incontinence/

2 Fry, Mike, "Reflections from the No Kill Conference in Washington DC":

animalarkshelter.org/animal/ArkArticles.nsf/AllArticles/3A078C33CD079D17862575AD00471A9B

3 James, Susan Donaldson (ABC News) "300,000 Imported Puppies Prompt Rabies Concerns"

October 24, 2007 petpac.net/news/headlines/importedpuppies/

4 Nolen, R. Scott "Rottweiler Study Links Ovaries With Exceptional Longevity"

JAVMA March 2010 avma.org/onlnews/javma/mar10/100301g.asp

5 Sanborn, Laura J., MS

"Long-Term Health Risks and Benefits Associated with Spay/Neuter in Dogs"; May 14,2007

naiaonline.org/pdfs/longtermhealtheffectsofspayneuterindogs.pdf

6 Thoms, Joy "The Importance of Spay-Neuter Contracts" The Orient Express, Nov, 2009

7 Waters, David J., DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVS "A Healthier Respect for Ovaries"

gpmcf.org/respectovaries.html

8 Winograd, Nathan J. "Debunking Pet Overpopulation" June 29, 2009

nathanwinograd.com/?p=1390

9 Winograd, Nathan, “Redemption: The Myth of Pet Overpopulation and the No Kill Revolution in America” Almaden Books, 2nd edition, Feb 25, 2009.

10 Zink, Christine, DVM, PhD, DACVP

"Early Spay-Neuter Considerations for the Canine Athlete"; 2005

http://www.thedogplace.org/Veterinary/0603-SpayNeuter_Zink.asp

11 “Retaining ovaries may be a key to prolonged life in women and dogs”; DVM Newsmagazine; Dec 5, 2009. veterinarynews.dvm360.com/dvm/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/646838

|

The Cruelty Of Castration

Barbara J. Andrews , Publisher TheDogPlace.org

June 2006 / What is the risk vs. benefit of surgically castrating your pet? Does “spaying” or “neutering” affect the health of your dog? Yes and Yes. Does castration have any health benefits? No. In fact female dogs and cats are the only creatures on the planet that routinely have their reproductive organs removed… The simple truth is there is no medical reason to remove reproductive organs from healthy animals; not in veterinary medicine and not in human medicine!

That’s why humans receive hormone replacement therapy (HRT) – to counteract the loss of vital sex hormones when women undergo hysterectomy or men are accidently castrated. Underproduction of estrogen and testosterone causes debilitating disease and premature aging in men and women. The demand for bio-identical hormone replacement therapy as a proven anti-aging therapeutic treatment for senior citizens has exploded. Hold that thought. You are one day older today than yesterday.

Are there health risks from neutering your dog? Absolutely. Can you look your dog in the eye and explain that slicing away what makes him a him is good for him? Castration is directly linked to heart disease, myocardial infarction, strokes and cardiovascular disease, senile dementia, osteoporosis and hip fracture. Hysterectomy risks in female dogs are intervertebral disk disease, Myasthenia Gravis, muscle weakness, a doubled risk of splenic hemangiosarcoma, and bladder and urinary tract infections are so common they are called “spay incontinence”. And as in male dogs, females have five times the risk of cardiac hemangiosarcoma Ref #1, 2 and both sexes suffer from lethargy, exercise intolerance, and obesity.

That’s not all. Neutered dogs of either sex are at double the risk for osteosarcoma and increased incidence of urinary tract cancers, Ref #3.

Facts. The deadliest cancers and the most annoying problem for house dogs are at the top of the list for spayed and neutered dogs. Removal of sex organs also significantly increases the odds of adverse reactions to vaccines (ref #4) and inclines both sexes to alopecia, hip dysplasia, and cruciate ligament rupture. You can cope with heat seasons easier than urinary incontinence, orthopedic problems, and cancer in your old dog.

Is the “right thing to do” painfully mutilating your dog or cat in order to prevent “overpopulation” when there are nearly 7 billion people reproducing at an incredibly reckless rate? The moral answer is No. Fencing your pet and being a responsible human makes much more sense.

Is there any upside to slicing out the testicles of male animals? Stallions have been turned into geldings and bulls into oxen since man first domesticated them. Castration makes males more manageable and steers gain weight faster. That’s it, except for being told that a dog with no testicles can’t get testicular cancer. The canine testicular cancer rate is so low that there are no valid statistics and the metastasis rate is only 15% when it is diagnosed. Castration to prevent ovarian or testicular cancer makes as much sense as removing the heart to prevent heart disease.

Animal Rights activists, ref #5, and HSUS (Humane Society of The U.S. which does not rescue, adopt, or shelter unwanted dogs) vow to stop all animal breeding. Their propaganda seeks to convince us that sterilization is “best for your pet”. The politically dangerous Animal Rights groups use mandatory spay/neuter law as a means of subverting citizen’s rights, property rights (yes dogs and cats are legal property) and our innate abhorrence to cruelty.

And sadly, we must thank the vet associations because spaying and neutering is nearly as profitable as treating the health problems neutered dogs develop. Is that why so many vets avoid informed consent and happily give in to owner and shelter requests to spay and neuter? Many vets welcome mandatory S/N law because it pumps the profit margin with hysterectomy/castrations and the myriad of health problems that follow!

Breeders buy into the castration complex because A. they want to maintain control over their bloodline and B. to eliminate competition from “irresponsible back yard breeders.” Those are noble and sensible reasons for requiring any dog not sold at “breeding” or “show” price to be sterilized but not from a health perspective. And it certainly makes no sense to the frightened, legs-crossed pet determined to remain as nature intended!

Is there an alternative to castrating my pet? Yes. If you are lucky enough to find a vet who will do tubal ligation or vasectomy, ref #6!!! As owners step away from the bonds of politically correct serfdom and demand ligation and vasectomy, cost will go down, more veterinarians will study and perfect safe, hormone preserving sterilization and dogs will no longer be forced to suffer the adverse effects and cruelty of sexual castration.

If you are lucky enough to have acquired a well bred purebred, please make an informed and loving decision. If you are still looking for a family pet and breeders are demanding spay/neuter, offer to pay extra to reserve the right to allow the dog to remain undamaged. It will be cheaper in the long run because you won’t have vet bills associated with castration health problems.

http://www.thedogplace.org/HEALTH/Cruelty-Castration_Andrews-1106.asp #1106

Ref #1 http://www.neutering.org/banes.html

Ref #2 http://www.neutering.org/files/LongTermHealthEffectsOfSpayNeuterInDogs.pdf

Ref #3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutering

Ref #4 http://www.thedogplace.org/VACCINES/Articles.asp

Ref #5 http://www.thedogplace.org/LEGISLATION/AR-Payoff-Congress-10062-Andrews.asp

Ref #6 Canine Tubal Ligation, Vasectomy

|

SPAY & NEUTER CONSIDERATIONS

Removal of Ovaries affects life span, how long dogs keep their ovaries determines how long they live! Early spay may be ill advised.

A Healthier Respect For Ovaries

by David J. Waters, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVS - TheDogPlace June 2011

A recent study by my research group appearing next month in Aging Cell reveals shortened longevity as a possible complication associated with ovary removal in dogs (1). This work represents the first investigation testing the strength of association between lifetime duration of ovary exposure and exceptional longevity in mammals. To accomplish this, we constructed lifetime medical histories for two cohorts of Rottweiler dogs living in 29 states and Canada: Exceptional Longevity Cohort = a group of exceptionally long-lived dogs that lived at least 13 years; and Usual Longevity Cohort = a comparison group of dogs that lived 8.0 to 10.8 years (average age at death for Rottweilers is 9.4 years). A female survival advantage in humans is well-documented; women are 4 times more likely than men to live to 100. We found that, like women, female Rottweilers were more likely than males to achieve exceptional longevity (Odds Ratio, 95% confidence interval = 2.0, 1.2 - 3.3; p = .006). However, removal of ovaries during the first 4 years of life erased the female survival advantage. In females, this strong positive association between ovaries and longevity persisted in multivariate analysis that considered other factors, such as height, adult body weight, and mother with exceptional longevity.

In summary, we found female Rottweilers who kept their ovaries for at least 6 years were 4.6 times more likely to reach exceptional longevity (i.e. live >30 % longer than average) than females with the shortest ovary exposure. Our results support the notion that how long females keep their ovaries determines how long they live.

In the pages that follow, I have attempted to frame these new findings in a way that will encourage veterinarians to venture beyond the peer-reviewed scientific text and data-filled tables of Aging Cell to consider the pragmatic, yet sometimes emotionally charged implications of this work. Call it a primer for the dynamic discussions that will undoubtedly take place, not only between practitioners and pet owners, but also within the veterinary profession. Call it a wake-up call for how little veterinarians have been schooled in the mechanistic nuts and bolts underlying the aging process. Call it an ovary story.

Do ovaries really promote longevity? Observed associations between exposures and outcomes may not necessarily be causal, so we explored alternative, non-causal explanations for the association between ovaries and exceptional longevity in our study. But we found no evidence that factors which may influence a pet owner's decision on age at ovary removal — for example, earlier ovariectomy in dogs with substandard conformation or delayed ovariectomy to obtain more offspring in daughters of long-lived mothers — could adequately account for the strong association.

There is another aspect of our data pattern that gives us further confidence that ovaries really do matter when it comes to successful aging. A simple explanation for the observation that ovaries promote longevity would be that taking away ovaries increases the risk for a major lethal disease. In Rottweilers, cancer is the major killer. We found, however, that by conducting a subgroup analysis that excluded all dogs that died of cancer, the strong association between intact ovaries and exceptional longevity persisted. After excluding all cancer deaths, females that kept their ovaries the longest were 9 times more likely to reach exceptional longevity than females with shortest ovary exposure. Thus, we observed a robust ovarian association with longevity that was independent of cause of death, suggesting that a network of processes regulating the intrinsic rate of aging is under ovarian control. This work positions pet dogs, with their broad range of lifetime ovary exposure, to become biogerontology's new workhorse for identifying ovary-sensitive physiological processes that promote healthy longevity.

Interestingly, our findings in dogs surface just as data from women are calling into question whether those who undergo hysterectomy should have ovary removal or ovary sparing. In fact, our results mirror the findings from more than 29,000 women in the Nurses’ Health Study who underwent hysterectomy for benign uterine disease (2). In that study, the upside of ovariectomy — protection against ovarian, uterine, and breast cancer — was outweighed by increased mortality from other causes. As a result, longevity was cut short in women who lost their ovaries before the age of 50 compared with those who kept their ovaries for at least 50 years. Taken together, the emerging message for dogs and women seems to be that when it comes to longevity, it pays to keep your ovaries.

But before we all go out and buy T-shirts with some romantic imperative like “Save the Ovaries”, perhaps we should step back and consider the following question: Why haven’t previous dog studies called our attention to this potential downside of ovariectomy? Reviewing the literature, an answer quickly bubbles up. No previous studies in pet dogs have rigorously evaluated the association between ovaries and longevity. Two frequently cited reports (3,4) provide limited guidance because: (1) longevity data are presented as combined mean age at death for a relatively small number of individuals of more than 50 breeds of different body size and life expectancy; and (2) ovarian status is reported as “intact” or “spayed”, rather than as number of years of lifetime ovary exposure. Comparing female dogs binned into the categories of “intact” versus “spayed” introduces a methodological bias that might lead one to conclude that ovaries adversely influence longevity, i.e. ovary removal promotes longevity. Because the reasons for ovariectomy (e.g., uterine infection, mammary cancer) increase with increasing age, it is expected that a large percentage of the oldest-dogs are binned as “spayed” despite having many years of ovary exposure. For example, a dog who at age 12 undergoes ovariohysterectomy for pyometra would be binned as “spayed”, despite 12 years of ovary exposure. In our study, we employed a more stringent study design — restricting the study population to AKC registered, pure-bred dogs of one breed, carefully quantitating the lifetime duration of ovarian exposure — in order to lessen the likelihood of such bias. And we reasoned that studying veterinary teaching hospital-based populations of dogs with artifactually low life expectancies (for example, 3.5 years is median age at death for Rottweilers in the Veterinary Medical Data Base)(5) was an inappropriate vehicle to describe the influence that ovaries have on aging. So we cast a wider net and collected data from Rottweiler owners nationwide, focusing our attention on exceptional longevity, not average age at death, as our study endpoint.

Why study exceptional longevity? Why not average longevity? We thought studying the most exceptionally long-lived individuals would tell us something about what it takes to age successfully. It’s the same rationale used by Thomas Perls and investigators of the New England Centenarian Study (6) and by other scientists who study long-lived humans in other parts of the world (7). The approach even garners support from the mathematical field. In a seminal book on the origins of creative genius, the mathematician Jacques Hadamard wrote: “In conformity with a rule which seems applicable to every science of observation, it is the exceptional phenomenon which is likely to explain the usual one.” (8) Hadamard was trying to understand how the brain gets creative so he studied people with extreme creativity. When it comes to studying aging, we’re solidly in the Hadamard camp. That is why in 2005 we established the Exceptional Longevity Data Base, launching the first systematic study of the oldest-old pet dogs (9). But folks in the opposing camp might justifiably fire back: “Don’t study extreme longevity. Extreme longevity is much more about luck than it is about genes, or environment, or ovaries.”

So to address the possibility that the “strangeness” or outlier nature of dogs with exceptional longevity could be forging a misleading link between ovaries and longevity, we studied a separate cohort of Rottweiler dogs. This data set was comprised of 237 female Rottweilers living in North America that died at ages 1.2 to 12.9 years — none were exceptionally long-lived. Information on medical history, age at death, and cause of death was collected by questionnaire and telephone interviews with pet owners and local veterinary practitioners. In this population, we found females that kept their ovaries for at least 4.5 years had a statistically significant 37% reduction in mortality rate (1). This translated into a median survival of 10.4 years for females with more than 4.5 years of ovary exposure — 1.4 years longer than the median survival of only 9.0 years in females with shorter ovary exposure (p < 0.0001). Taken together, if you take out ovaries before 4 years of age you cut longevity short an average of 1.4 years and decrease the likelihood of reaching exceptional longevity by 3-fold.

Up to this point, my ovary story has centered around a summarizing of methodologies and results. The reader has been given opportunity to see the gist of our findings within the context of previous dog studies and late-breaking studies in women. Now, let us pivot our attention a bit away from the results to focus on the recipients of these results — DVMs and pet owners.

We can start by tackling the question: Just how receptive will DVMs be to these new research findings? It’s hard for old dogs to learn new tricks. But one thing is sure — blossoming change is rooted in real communication. The anthropologist Gregory Bateson wrote: “The pre-instructed state of the recipient of every message is a necessary condition for all communication. A book can tell you nothing unless you know 9/10ths of it already.” (10). I call this “Bateson’s Rule of the 9/10ths”. If Bateson is right, then we will want to do something about the pre-instructed state of veterinarians. Because when it comes to the biology of aging, the state is virtually a blank slate. None of us received training in the biology of aging as part of our DVM curriculum — whether we graduated 30 years ago or last summer. Therefore, most DVMs are ill-prepared to receive messages examining the mechanistic underpinnings of the aging process. A Batesonian prescription for positive change would be to ratchet up the biology of aging IQ of practicing veterinarians. We agree. That is why we established the first gerontology training program for veterinarians in 2007 (11). We believe that by helping veterinarians “know” more about aging, they will be more able and more receptive to communicating the things that promote healthy longevity in their patients — things like preserving ovaries.

For certain, DVMs will be asked by pet owners to help them make their decision about age at spay in light of this new information. The question will be asked: Just how generalizable are these findings in Rottweilers to other segments of the pet dog population? It is impossible to say at this time. It will demand further study. Alas, 10 years from now, we might just find out that a longevity-promoting effect of ovaries in dogs is limited — limited to large breeds, urban but not rural dogs, or only those individuals with particular polymorphisms in insulin-like growth factor-1. These restrictions should not only be expected, they should be celebrated. It will mean that we have looked more deeply into how ovaries might influence healthy longevity. It will mean that our initial findings have been contextualized. And it is this contextualization of information that marks scientific progress — the kind of progress that guides sound clinical decision making. For it is context that determines meaning (12).

Our provocative findings in Aging Cell mean that it’s time to re-think the notion that taking away ovaries has no significant downside to a dog’s healthy longevity. Perhaps it would help us if we thought of lifetime ovary exposure as information — information that instructs the organism. Just how long and how healthy a female lives reflects what her cells, tissues, and organs thought they heard from the message received. Of course in biology, there is no single message but a symphony of messages, enabling each individual to successfully respond to environmental challenges. Our findings suggest that ovaries orchestrate that symphony. Taking away ovaries in early or mid-life makes for muddled information, less than perfect music.

Information muddling can ensnarl decision-making. Our research takes an important first step toward disentangling the thinking about ovaries and longevity. We must never be paralyzed by the incompleteness of our knowledge. Our knowledge will always be incomplete — subject to revision, primed for further inquiry. This uncertainty, although invigorating for the investigator, is often painful for the practitioner who seeks simple, fact-driven algorithms to guide his action. Just as scientists will be called upon to forge ahead with their scientific inquiries, so too will practitioners be counted on to master the uncertainty. Together, we must navigate what the Danish philosopher-theologian Soren Kierkegaard called the gap “between the understanding and the willing.” That is, we must ask the right questions and make smart choices so that our action (the willing) is in synch with our knowledge (the understanding). Under just what circumstances will a particular individual benefit from specific lifestyle decisions? This is perhaps the most prescient, overarching question in the wellness and preventive medicine fields facing both human and veterinary health professionals today. How can we promote healthy longevity? Antioxidant supplementation or calorie restriction? Ovary removal or ovary sparing?

Undoubtedly, there will be protagonists and antagonists in this ovary story. The protagonists will be open-minded to following a new script. They will embrace the idea of ovary sparing for critical periods of time to maximize longevity. They might even recognize the need for some sort of “ovarian mimetic” in spayed dogs to optimize healthy aging. The antagonists in this story — the defenders of the old script — will dismiss as trivial the notion that ovaries regulate the rate of aging and influence healthy longevity. Lines will be drawn and opinions will fly. But that's what healthy debate is — antagonists and protagonists keeping a high priority issue front and center, not allowing it to fade into the woodwork. It would seem that, in light of the new scientific findings, a contemporary dialogue should balance the potential benefits of elective ovary removal (13) with its possible detrimental effects on longevity.

http://www.thedogplace.org/HEALTH/Respect-Ovaries_Waters(Jordan)-1106.asp #1106

References:

1. Waters DJ, Kengeri SS, Clever B, et al: "Exploring the mechanisms of sex differences in longevity: lifetime ovary exposure and exceptional longevity in dogs." Aging Cell October 26, 2009

2. Parker WH, Broder MS, Chang E et al: "Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy and long-term health outcomes in the Nurses' Health Study." Obstet Gynecol 113: 1027-1037, 2009

3. Bronson RT: "Variation in age at death of dogs of different sexes and breeds." Am J Vet Res 43: 2057-9, 1982

4. Michell AR: "Longevity of British breeds of dog and its relationships with sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease." Vet Rec 145: 625-629, 1999

5. Patronek GJ, Waters DJ, Glickman LT et al: "Comparative longevity of pet dogs and humans: implications for gerontology research." J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 52: B171-8, 1997

6. Perls TT, Hutter Silver M, Lauerman JF: Living to 100: Lessons in Living to Your Maximum Potential at Any Age, New York, NY, Basic Books, 1999

7. Franceschi C, Motta L, Valensin S et al: "Do men and women follow different trajectories to reach extreme longevity?" Aging (Milano) 12: 77-84, 2000

8. Hadamard J: The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field. New York, NY, Oxford Univ Press, 1945, p. 136

9. Waters DJ, Wildasin K: "Cancer clues from pet dogs." Sci Am 295: 94-101, 2006

10. Bateson G, Bateson MC: Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. New York, NY, Bantam, 1988, p 163

11. Gerontology Program for DVMs co-sponsored and organized by Gerald P. Murphy Cancer Foundation, Purdue University Center on Aging and the Life Course, P&G Pet Care; for more information go to www.gpmcf.org

12. Waters DJ, Chiang EC, Bostwick DG: "The art of casting nets: fishing for the prize of personalized cancer prevention." Nutr Cancer 60: 1-6, 2008

13. Kustritz MV: "Determining the optimal age for gonadectomy of dogs and cats." J Am Vet Med Assoc 231: 1665-75, 2007

http://www.gpmcf.org/respectovaries.html

|